Organ of the month: Mammary Glands

I. Indications for biopsy/pathological evaluation

Mammary lesions are among the most common samples submitted to veterinary diagnostic pathology laboratories, as they are very common in dogs and, to a lesser extent, cats. The vast majority of mammary samples are submitted to investigate masses (or cysts) and, when present, to type and grade mammary neoplasms. This also allows evaluation of margins and any local draining lymph nodes submitted concurrently.

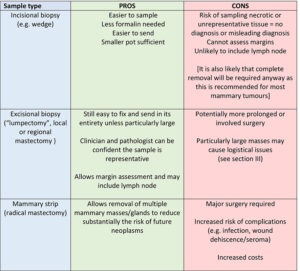

II. Different types of biopsy (Table 1)

Table 1. Pros and cons of various mammary gland sampling methods

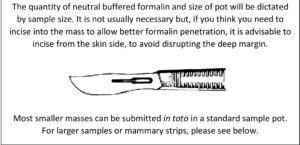

III. How to prepare and send mammary samples – a few tips

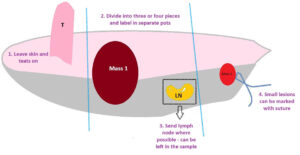

To assist with orientation (see Fig 1):

- Leave skin attached – this also helps with margin assessment.

- Large samples can be split into three or four pieces, e.g. a mammary strip could be divided into cranial, middle and caudal. Please make sure pots are clearly labelled. Photographs can be very helpful. We cannot discern cranial, caudal, left and right without clear indicators so, if this is important to you, please let us know. Bear in mind that, while a single large mass could be divided into, say, four quarters, this can make it difficult to identify margins post fixation.

- Send lymph node where possible (especially for cats) and let us know you have done this.

- pecific areas of interest can be marked with a suture.

- Also please refer to Finn Factsheet No. 91

Fig 1. Orientation tips for mammary strip

IV. Relevant clinical information

a) A brief general clinical history is usually sufficient, along with signalment.

b) Any results of previous tests such as FNAs, is also helpful.

c) Consider taking photographs at time of sampling as colours and textures change with fixation.

V. Effects of ovariohysterectomy 2,3

Ovariohysterectomy (OVH) at a young age has a substantial effect on the development of mammary neoplasia. This effect is most pronounced when dogs are spayed prior to their first oestrus cycle. The risk of developing a mammary tumour after that is 0.5%. Spaying before the second and third season also has a protective effect, but decreasingly so. The same effect is present in cats spayed at a very young age, and neutering at any age decreases the risk of mammary neoplasia in cats by up to 60%. The incidence of mammary neoplasia is seven times higher in intact female cats compared to those that have been ovariectomised. In dogs, the caudal glands are most frequently affected and 50% of mammary tumours are benign. In cats, more than 85% of mammary tumours are malignant and most are aggressive.

VI. Histological examples of selected mammary neoplasms

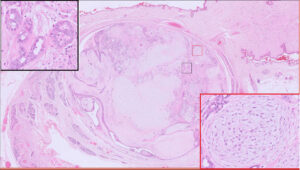

Fig 2. Complex mammary adenoma, canine – this contains both epithelial cells (top left inset) and myoepithelial cells (bottom right inset). This is one of the most common benign mammary tumours we see in the dog. It is well-demarcated and compressive – classical features of a benign neoplasm.

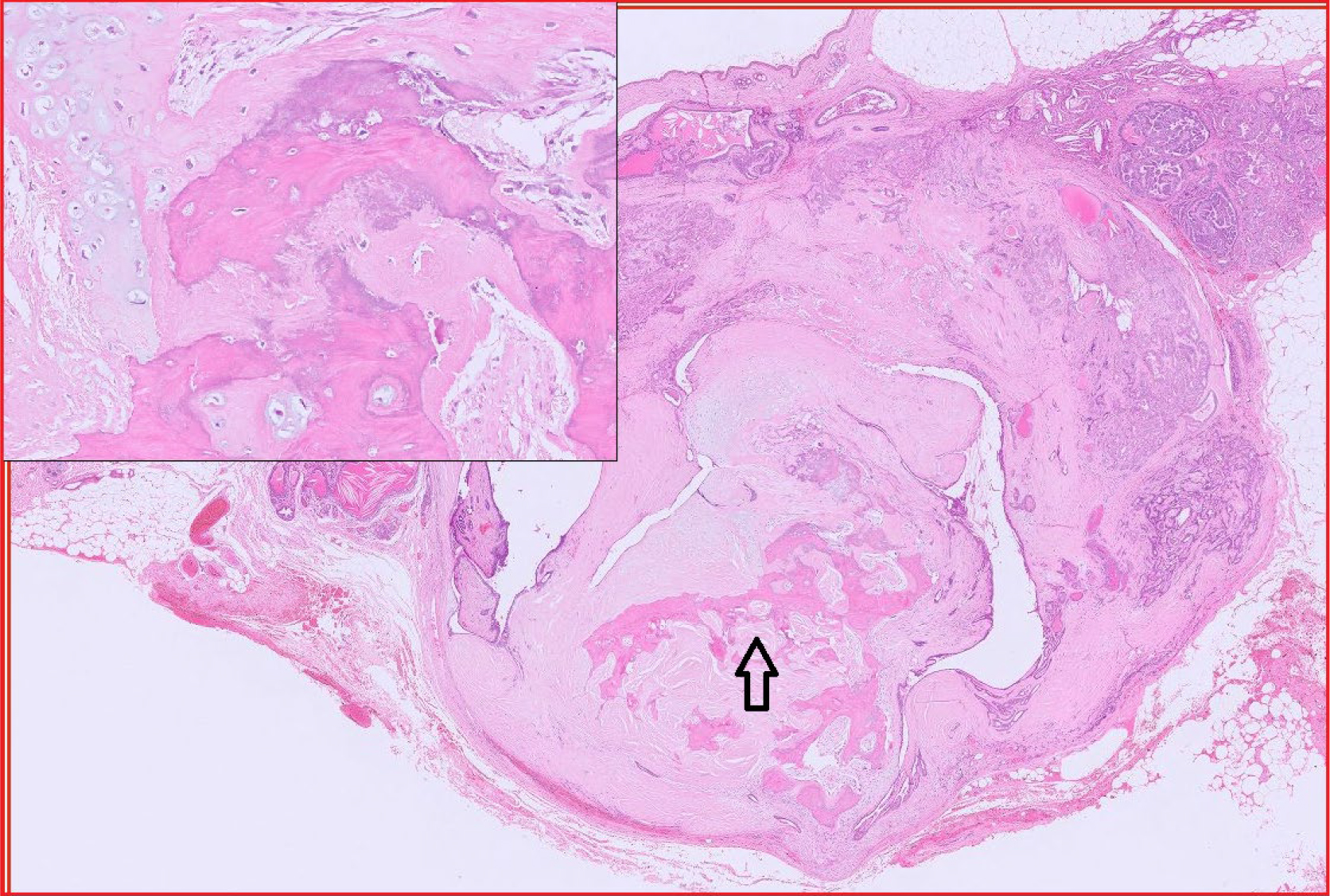

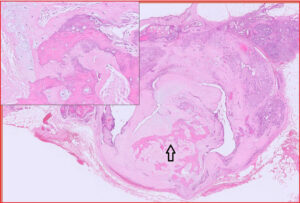

Fig 3. Benign mixed mammary tumour, canine. This is another common mammary tumour in the dog. It differs from the complex mammary adenoma in that it contains bone and/or cartilage (inset). Arrow = bone.

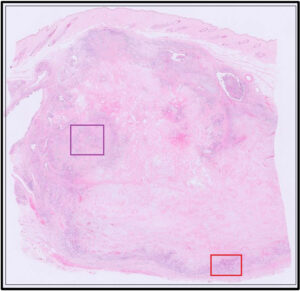

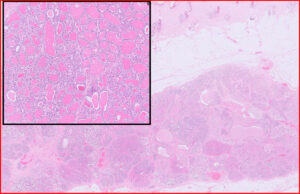

Fig 4. Mammary carcinosarcoma, canine. This is an uncommon mammary neoplasm that is unfortunately very aggressive. It is composed of epithelial and mesenchymal cells and both populations are malignant. The mesenchymal component can also produce osteoid and/or chondroid matrix, i.e. forming a chondrosarcoma or osteosarcoma. The epithelial cells metastasise via lymphatics vessels to regional lymph nodes and the lungs, while the mesenchymal cells spread haematogenously to the lungs. Much of this particular example is necrotic.

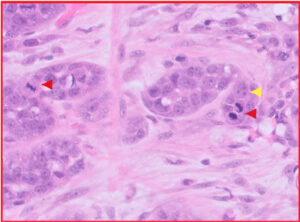

Fig 5. Red box from Fig 4, illustrating epithelial cells with features of malignancy (red arrowhead = mitoses; yellow arrowhead = multiple nucleoli). There is also a fairly high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, moderate anisokaryosis and nuclear atypia.

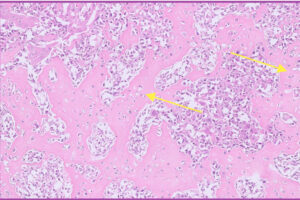

Fig 6. Purple box from Fig 4, illustrating mesenchymal cells and production of tumour-associated osteoid matrix (yellow arrows), sufficient for a diagnosis of “osteosarcomatous” differentiation within this carcinosarcoma.

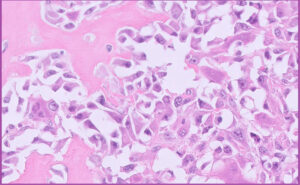

Fig 7. Higher magnification of neoplastic mesenchymal cells from Fig 6 above.

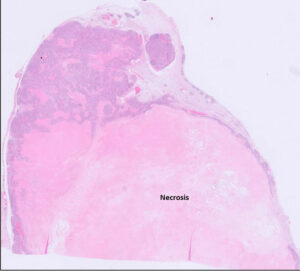

Fig 8. Feline mammary carcinoma (solid type with lots of necrosis).

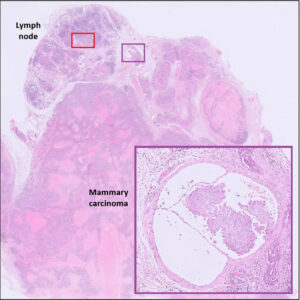

Fig 9. Same tumour as Fig 8 including lymph node. [Inset = lymphatic invasion]

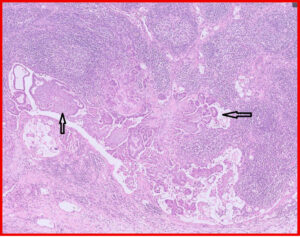

Fig 10. Red box from Fig 9. Neoplastic cells are present in the lymph node sinus, indicating metastasis (black arrows)

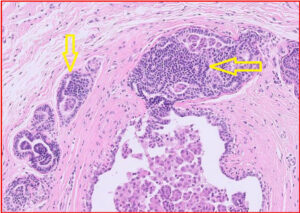

Figs 11A and B. Not all lesions are neoplastic.

11A: Mammary lobular hyperplasia, canine

11B: Mammary epitheliosis (yellow arrows), canine. This is believed to be a precursor to carcinoma.

In cats, one of the more common non-neoplastic lesions we see in the mammary area is duct ectasia, with or without inflammation. This can create a “spongy” texture within the mammary area. While we do see mastitis from time to time, this is much less common in companion animal species.

References

- https://www.finnpathologists.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/FINN-Fact-Sheet-9-Submission-of-Challenging-Samples-Issue-2-04.07.2023-1.pdf

- https://www.acvs.org/small-animal/mammary-tumors/

- Goldschmidt et al In Tumors in Domestic Animals. Ed. DJ Meuten. pp723-765.

Related Posts

Organ of the Month: Mammary Glands

Organ of the month: Mammary Glands I. Indications for biopsy/pathological evaluation Mammary lesions are among…

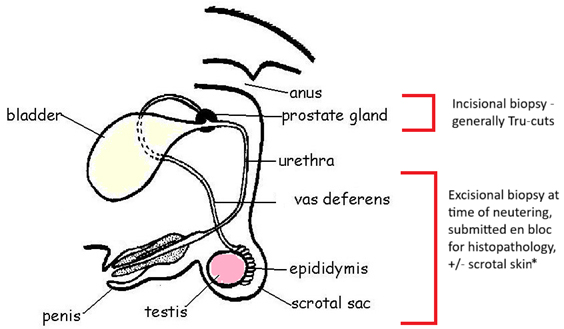

Organ of the Month: PART II – The Male Reproductive Tract

Organ of the month: PART II – The Male Reproductive Tract I. Indications for biopsy/pathological…

Diagnosis of Canine Hypercortisolism

Diagnosis of Canine Hypercortisolism Introduction Hypercortisolism is a common endocrinopathy in dogs and is also…

Canine and Feline Blind Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL)

Canine and Feline Blind Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL) Common indications for blind BAL: Chronic cough Chronic…