Organ of the month: Oral

I. Indications for oral biopsy

Oral biopsies are among the most common samples received by commercial diagnostic laboratories and the most common reason for biopsy is an oral mass (or masses). Other reasons for sampling may include significant periodontal disease, gingivostomatitis, or perhaps cystic lesions. Histopathology is the gold standard for reaching a diagnosis and it is important to keep in mind that many lesions appear similar, whether inflammatory, benign or malignant.

II. Different types of biopsy - pros and cons

As with most organs and tissues, the two main types of biopsy are incisional and excisional. Incisional oral biopsies are most common, mainly because (i) they are easier to collect in this more awkward part of the body and (ii) they allow initial diagnosis and decision-making prior to undertaking anything more radical.

III. How to sample and send oral samples

It is obviously beyond the scope and expertise of this article to cover surgical techniques but suffice to say that oral soft tissues (e.g. buccal mucosa, gingiva, fauces) are prone to crush artefact and some lesions are very friable. If sampling is not undertaken with care, crush artefact can preclude a conclusive diagnosis. It is also important to bear in mind that surface lesions may only be the “tip of the iceberg” such that biopsy alone may not be sufficient, but best undertaken in conjunction with imaging, to assess deeper tissues and bone. Where possible, multiple samples should be taken to ensure the biopsies are as representative as possible. Samples should be submitted in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Oral lesions should be sampled intraorally so that lip tissue remains intact (may be required later for reconstruction)1.

Radical tumour resection from the oral cavity is likely to involve sampling and/or removal of bone. Most of the larger oral samples we receive originate from referral practices, since this typically requires specialised surgical techniques. If submitting these types of samples, bear in mind that a period of decalcification will be required and this can be prolonged, depending on sample size, location and signalment of the animal (e.g. maxilla from an adult male Rottweiler will take much longer to process than a pathologically softened mandible from a cat). We further dissect most of these samples at the laboratory but even small or thin portions of bone require a period of softening prior to cutting with the microtome.

Particularly if orientation is not obvious – and bear in mind samples change consistency, colour and even shape during fixation – it can be very helpful to add orienting sutures or surgical ink to margins and areas of interest. Sending photographs of the lesion in situ and following resection is also very useful to the pathologist. Where possible, it is best to avoid using thermal cautery as this can create significant artefact and hamper margin evaluation.

IV. Relevant clinical information

The most helpful information you can provide with oral samples includes:

- Signalment (as with any biopsy)

- Location, size and number of lesion(s); shape and colour can also be very helpful, especially if papilliferous and exophytic (outwardly growing), or invasive

- Duration and progression

- Imaging information is particularly useful (i.e. CT and/or radiographs)

- For cystic lesions, how they relate to associated teeth (including unerupted teeth) is valuable ancillary information

V. Common diagnoses in cats and dogs

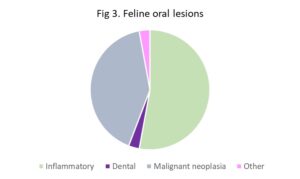

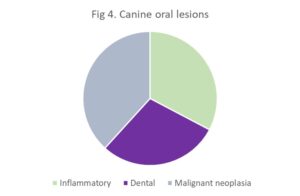

While oral lesions are common in dog and cat, the majority are benign and inflammatory. The pie charts below summarise the percentage of diagnosis in cats and dogs (Figs 3 and 4), derived from a recent review of such lesions2. While malignant neoplasms accounted for ~40% of feline oral lesions, this was mostly due to squamous cell carcinoma, the most common oral neoplasm in cats. More significantly, note that inflammatory lesions were even more common, accounting for around half the feline oral submissions in that study. In the same study, canine oral lesions were evenly distributed between inflammatory, odontogenic and malignant neoplasia. Malignant melanoma and fibrosarcoma were the top two canine oral malignancies but odontogenic neoplasia was more common compared to the cat, particularly fibromatous epulides of periodontal ligament origin (also known as peripheral odontogenic fibromas). While studies vary in fine detail, broad patterns are similar3.

VI. Histopathological examples

It is not the purpose of this article to illustrate the full gamut of oral lesions but a select few below aim to highlight some specific points.

Figs 5A and 5C. Below are oral lesions from two different cats, both on the tongue. Figs 5B and 5D are high power views of 5A and 5C, respectively. Fig 5B is an eosinophilic granuloma (yellow arrow points to focus of collagenolysis caused by degranulating eosinophils and is rimmed by a granuloma). Fig 5D is a fibrosarcoma. These lesions are obviously very different in terms of likely behaviours, outcome and management, but they may appear similar grossly and even on low magnification.

Fig 6 illustrates how immunohistochemistry (IHC) may be required to reach a definitive diagnosis. Clockwise from top left: Standard haematoxylin and eosin (HE) at low magnification; HE at high magnification (no melanin!); IHC using Melan A, an antibody marker of melanocytes. This helped to confirm the suspected oral amelanotic melanoma.

Key take home messages:

- Histopathology is the gold standard test for diagnosis of oral lesions

- Small or superficial samples may not be representative of deeper changes – inflammation and hyperplasia may be superimposed on malignancy, for example. [See appendix at end for example of inconclusive biopsy]

- Imaging is a key modality in the investigation of oral lesions in dogs and cats

References

- https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/mastering-oral-biopsies-dogs-cats-stratocyte-2qqdc

- Wingo K (2018) Histopathologic Diagnoses From Biopsies of the Oral Cavity in 403 Dogs and 73 Cats. J Vet Dent 35:7-17.

- Svendenius L and Warfvinge G (2010) Oral Pathology in Swedish Dogs: A Retrospective Study of 280 Biopsies. J Vet Dent 27:91-97.

APPENDIX EXAMPLE

The images below are of an oral lesion from a 12Y cat. While they comprise a florid polypoid epithelial lesion, with features consistent with chronic hyperplastic gingivitis, we could not conclusively exclude squamous cell carcinoma.

Appendix B: Higher power image of area in blue box (Appendix A above). While there are islands of squamous cells in the stroma, they are not particularly atypical and could be invaginations from the hyperplastic mucosal epithelium, rather than truly invasive neoplastic cells. However, the yellow arrow highlights an atypical surface epithelial cell that raises some suspicion of malignancy (or at least squamous cell carcinoma in situ, where the neoplastic cells are restricted to the mucosal epithelium and have not yet invaded). See higher power image of this cell in Appendix C.

Appendix C: Very atypical surface epithelial cell in the gingival mucosa with atypically large nucleus and large nucleolus. Dysplasia secondary to inflammation can cause atypia but this is extreme even for that. The final diagnosis was marked chronic active, hyperplastic stomatitis with atypia. In cases such as this, close monitoring, radiographs and resampling as necessary are generally suggested.

Related Posts

Organ of the Month: Skin

Organ of the month: Skin I. Indications for skin biopsy Skin biopsies account for a…

Organ of the Month: Oral

Organ of the month: Oral I. Indications for oral biopsy Oral biopsies are among the…

Organ of the Month: Spleen

Organ of the month: Spleen I. Indications for splenic biopsy Due to the nature of…

Organ of the Month: Gastrointestinal Disease

Gastrointestinal Disease: How can Laboratory Tests Help? A recent “Organ of the Month” outlined how…