Organ of the month: PART I – The Female Reproductive Tract

I. Indications for biopsy/pathological evaluation

As a reminder, the female reproductive tract is composed of the ovaries, uterine tubes (oviducts), ovarian bursa, uterus, cervix, vagina and vulva. The uterus is composed of uterine horns, bifurcation and uterine body. Histopathological evaluation of the female reproductive tract may be required for the following reasons:

a) Abnormalities detected at time of neutering

b) Concern regarding neoplasia, cysts or other mass effects detected clinically

c) Investigation of abnormal haemorrhage or discharge

d) Investigation of potential sexual hormone abnormalities

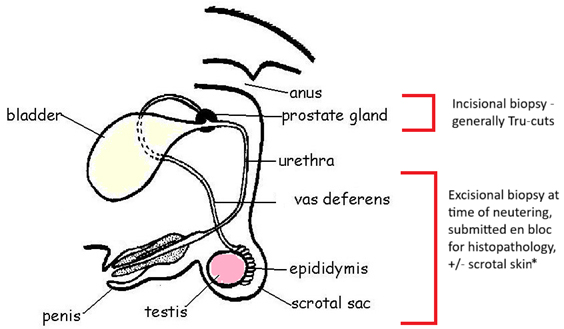

II. Different types of biopsy

Reproductive tract

While potentially feasible, we are not normally sent incisional biopsies of female reproductive tract from general practitioners. It is more likely that such a technique would be used to investigate reproductive issues in breeding animals, alongside cytology and bacterial culture1. At least for small companion animals, if all other conditions allow, it makes more sense to neuter the animal and send the bulk of the reproductive tract, i.e. from ovaries to uterine body, for pathological evaluation. If you are only interested in one ovary (for example) or a localised lesion, it is also fine to isolate that following ovariohysterectomy (OVH) and send that particular area.

III. How to sample and send reproductive tract samples

A. Once removed, open the uterine horns, especially if distended with pus. Take care not to cause clamp-related crush injury, particularly in the location of a suspected lesion.

B. Tag any lesions of interest with suture. They may look obvious at time of surgery but formalin changes the colour.

Lesion before fixation – very obvious!

Lesion after fixation – easier to overlook, especially if small. Suture tags help avoid this.

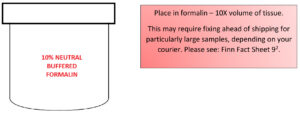

C. Fixation – the entire uterus and ovaries can be fixed in one piece.

Once received, we take a standard set of sections from an OVH submission as outlined in Fig 1, plus any grossly visible lesions.

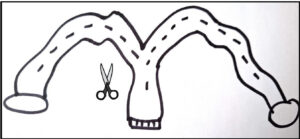

Fig 1. Standard sections taken for histopathology.

Yellow = uterine stump; Red = uterine body; Green = uterine bifurcation; Blue = uterine horns; Pink = ovaries. Plus any other grossly visible lesions.

D. Relevant clinical information

a) Signalment: Reproductive neoplasia is more likely in older animals so the age of the animal is helpful.

b) Brief summary of clinical signs and reasons for sampling.

c) Results of other tests, e.g. CBC/biochemistry, FNAs, imaging of visceral organs, any hormonal testing.

d) Consider taking photographs at time of sampling as colours and textures change with fixation.

E. Diagnoses in female reproductive tract submissions

The most common conditions we see affecting the female reproductive tract are (not in any particular order):

• ovarian and parovarian cysts;

• pyometra and/or cystic endometrial hyperplasia;

• uterine adenomyosis*; and

• ovarian neoplasia.

Uterine neoplasms are less common, with the exception of smooth muscle tumours (leiomyoma/sarcoma). Ovarian inflammation is also uncommon. A few histological examples are illustrated in section VI.

*Adenomyosis is a condition whereby endometrial tissue is present in the wall of the uterus, i.e. the myometrium. It is somewhat analogous to endometriosis and is often incidental. The exact cause is uncertain. Some authors believe it may be an artefact of fixation and this is one reason why opening the uterus prior to fixation is considered to be important3.

F. Histopathology of selected female reproductive tract lesions

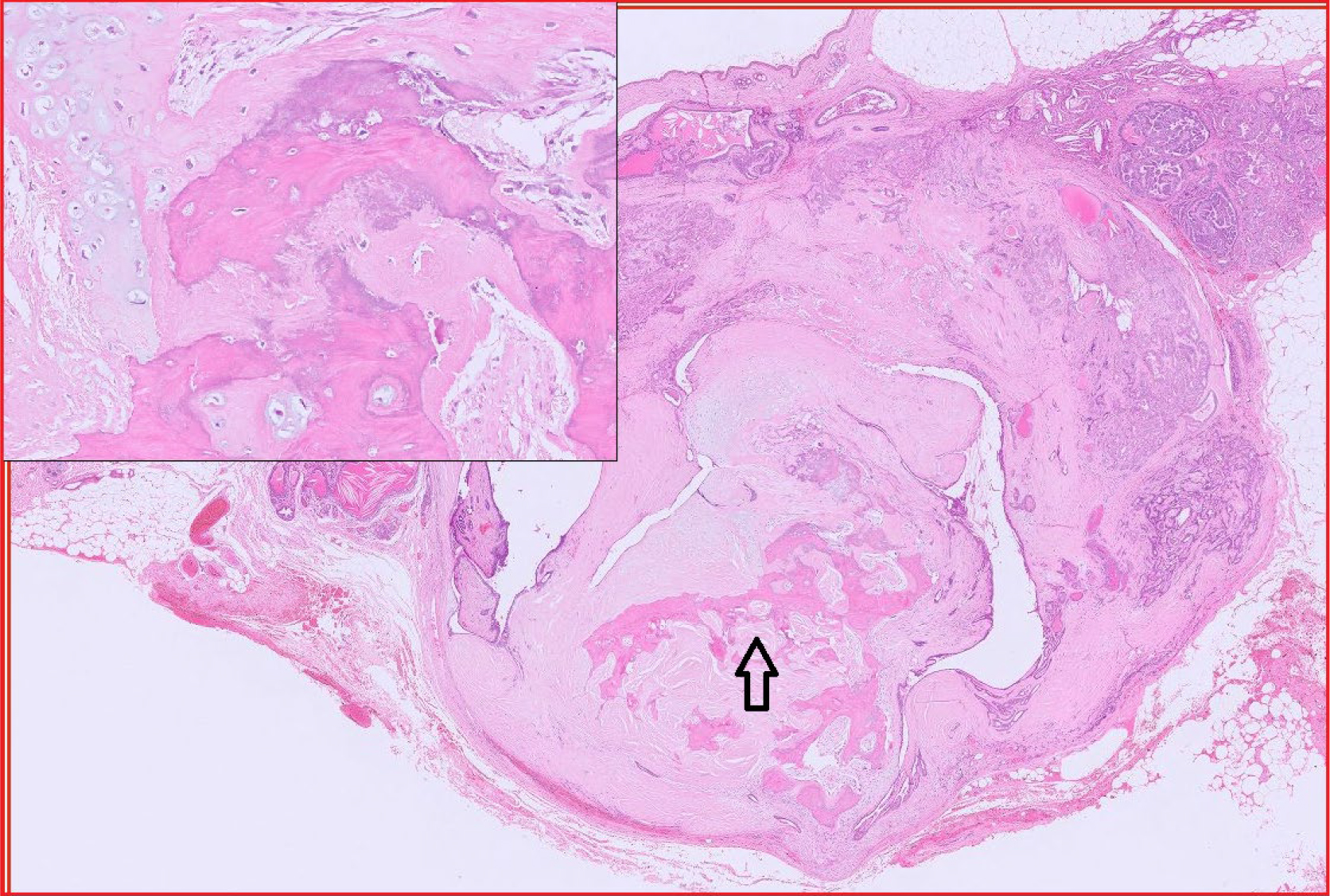

Fig 2a. Canine cystic endometrial hyperplasia and pyometra. The endometrium is very thickened due to increased numbers of glands (hyperplasia) and cystic distension of many of these glands. The cystic glands and uterine lumen are filled with large numbers of neutrophils (pyometra). Yellow box in Fig 2b below.

Fig 2b. Canine cystic endometrial hyperplasia and pyometra. Cystic endometrial glands filled with neutrophils. Cystic endometrial hyperplasia occurs under the influence of progesterone following priming with oestrogen. Affected individuals may experience pseudopregnancy and affected uteri are prone to pyometra.

Fig 2c. Canine cystic endometrial hyperplasia and pyometra. Intraluminal pus composed of large numbers of neutrophils.

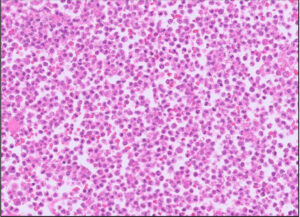

Fig 3. Ovarian granuloma cell tumour (probably the most common ovarian neoplasm we see in canines, anecdotally)

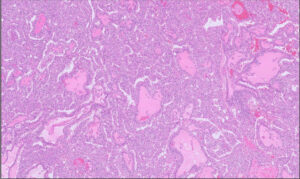

Fig 4. Ovarian epithelial neoplasm. The pattern is much more tubulopapillary. Distinguishing benign from malignant is tricky but breaching of the ovarian surface is a sign of malignancy.

Fig 5. Ovotestis in a dog. This is a much more unusual finding. Testis (degenerate seminiferous tubules) on the left and ovary on the right. *** denotes an ovarian follicle.

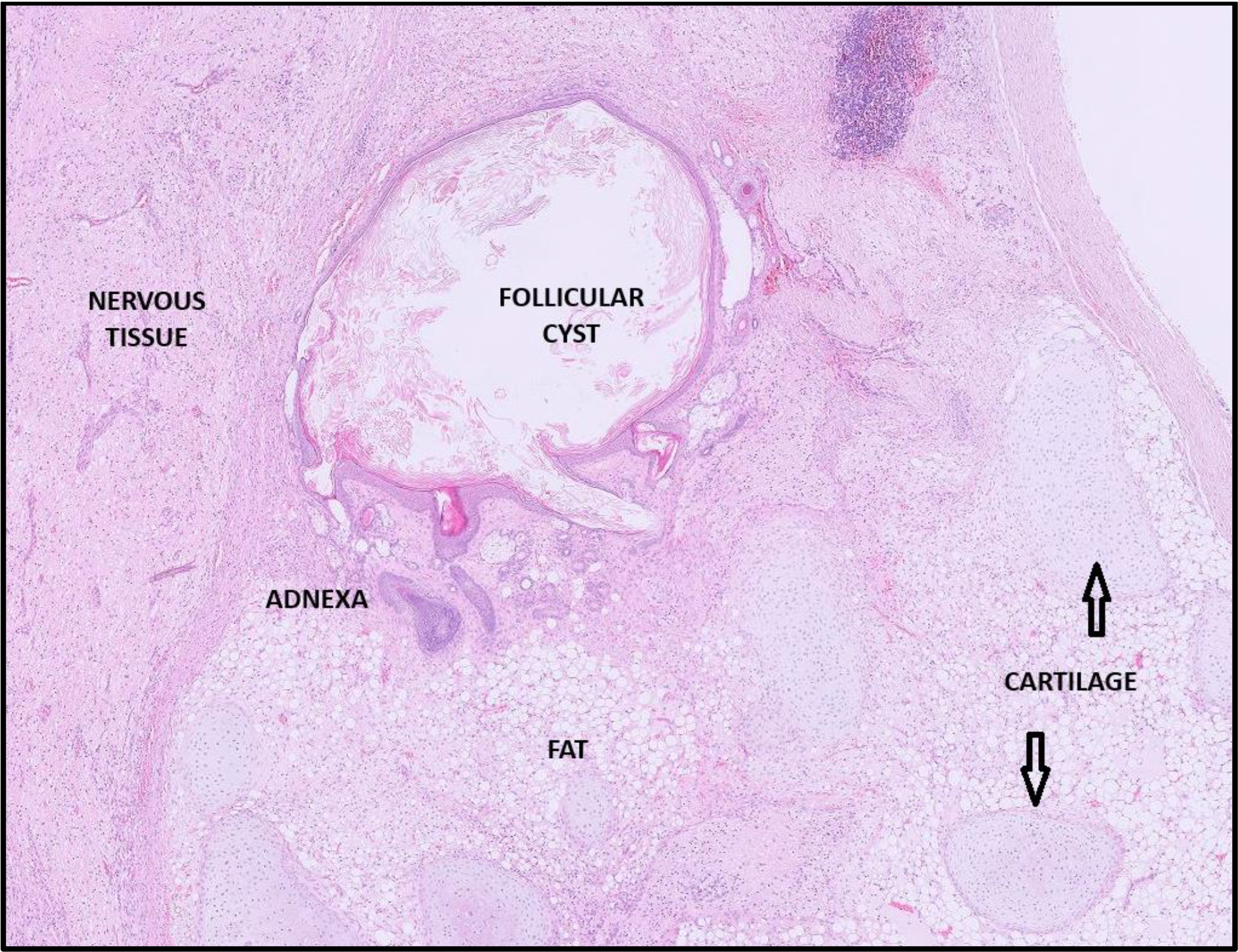

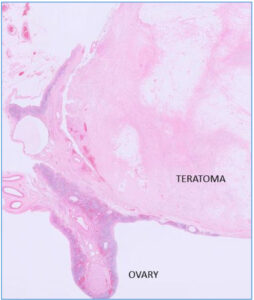

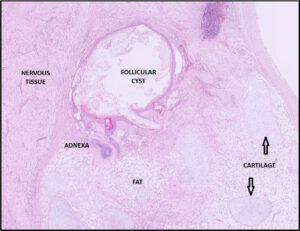

Fig 6-10. Ovarian teratomas

This is the strangest of tumours so has to be included in a segment on ovarian neoplasia! Teratomas are defined as neoplasms composed of cells derived from at least two, often three, embryonic germinal layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm). They are presumed to arise from the pluripotent germ cells that undergo differentiation. They are very uncommon but most commonly described in female dogs. The images in the cases below contain a keratinised cyst, lobules of fat, respiratory epithelium, hair shafts, neuropil with neurons, fat and cartilage. We can sometimes see bone or rudimentary teeth.

Fig 6. Ovarian teratoma

Fig 7. Some cysts within the teratoma are lined by respiratory epithelium

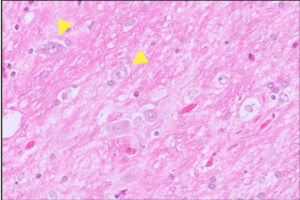

Fig 8. Blue box around some hair shafts. Yellow box around nervous tissue (see Fig 9).

Fig 9. In Fig 9 the yellow box surrounds nervous tissue containing neurons (yellow arrowheads).

Fig 10. Ovarian teratoma from a different dog.

References

- Root Kustritz MV (2006) Collection of tissue and culture samples from the canine reproductive tract. Theriogenology 66:567–574.

- https://www.finnpathologists.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/FINN-Fact-Sheet-9-Submission-of-Challenging-Samples-Issue-2-04.07.2023-1.pdf

- McEntee K (1990) Reproductive Pathology of Domestic Mammals. Academic Press p 158-159.

Related Posts

Organ of the Month: Mammary Glands

Organ of the month: Mammary Glands I. Indications for biopsy/pathological evaluation Mammary lesions are among…

Organ of the Month: PART II – The Male Reproductive Tract

Organ of the month: PART II – The Male Reproductive Tract I. Indications for biopsy/pathological…

Diagnosis of Canine Hypercortisolism

Diagnosis of Canine Hypercortisolism Introduction Hypercortisolism is a common endocrinopathy in dogs and is also…

Canine and Feline Blind Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL)

Canine and Feline Blind Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL) Common indications for blind BAL: Chronic cough Chronic…